News

Made in England: A Perilous Beginning - Chapter 1 - Made in England - The Memoirs of Dr Choudry Mohammed Walayat MBE

Half an hour after I was born, my young mother died. I was her first, and now her only, child and my father, a clerk at a brick-making kiln, was devastated with grief at the loss of a much-loved wife. My grandmother, Mirza Bibi, was overjoyed when she heard the news of my birth at her own village six miles away, but on her way over a messenger intercepted her to tell her the dreadful news that her daughter had died in childbirth. She had already lost a son and now she was to be so tragically bereaved again.

In this desperate, and extremely sad, manner I was welcomed into the world on 10th September 1936. It could have been my last day on earth as well, because when relatives and neighbours brought sacks of wheat grains to mark the death of a much loved person, as is the custom in our country, they piled the sacks high unaware that I had been lain down in a “perri” (a traditional stool with a wicker base slung on four protruding legs) alongside the pile. Concentrating on their condolences to my dead mother, who was only in her late teens, they forgot about me. As the relatives piled on ever more grain sacks, the pile continued to grow into a heap of considerable size. Suddenly it collapsed over where I was lying, and it could have squashed and suffocated me to death. I was saved by the wooden frame and a shallow depression in the wicker covering of the perri, that just kept the sacks off my tiny body.

Such is life, where ill-fortune and good luck come in varying proportions, and that day I was spared to live a full, and I hope useful, life which so far has spanned seventy two years. I was, of course, unaware at the time of the momentous events that were about to unfold in the next decade in my country, leading to the splitting of the subcontinent in 1947 into Pakistan, East and West, and Congress-ruled India.

In the year I was born, in a small village in south western Kashmir called Dhangry Bahdur in the Mirpur District, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the Mumbai barrister and the leading figure in the founding of Pakistan, having realised how badly the Muslim population of India would do in the elections that followed the new colonial constitution of 1935, took the Muslim League out of the Congress Party. From that date the Muslim League decided to fight all future local and national elections as a separate Muslim political party. So in 1936 the real countdown to the formation of my country of Pakistan began.

|

| My father Haji Mohammed

Abdullha, when he visited Britain in 1979, photographed with my children Kashaf, Indleeb, Nadeem and Ambreen. |

I was born into a Kashmir that was not part of the British Raj, but rather a princely state ruled by its own Maharajah, the unpopular Harri Singh who was a Hindu and whose family had bought Kashmir off the British in 1846. While many areas of Kashmir enjoy some of the most spectacular mountain scenery in the world, where the Himalayas form the northern part of the state, our village of only about fifteen houses and probably only forty people was on the plains twenty miles from the Jhelum River, which would later form the border of the new state of Pakistan when partition came in 1947.

The house of my father, Mohammed Abdullha, was a typical single room,

flat roofed, mud brick affair, even though he was a “Munshi”, a man with some

education, who had a reasonably prestigious job as a clerk at the kilns

belonging to a Hindu brick maker near to our village. Almost all the people in

the village were Jats by caste, including my family, and they traditionally are

a farming caste and so most of the men in the village were farmers or

agricultural labourers. We were surrounded by small fields that produced

wheat and vegetable crops, for

that part of Kashmir is very

fertile, and most families had a

few animals. We had sheep,

goats and the odd cow and

oxen, but we all lived in one

room. If there was a second

room to a house it was used to provide shelter for the animal. We only had the one room and, of course, there

were no modern facilities like electricity or water on tap, although you could

live out of doors in the compound around your house nearly all of the year.

Later, when living in England, I became an indoor person, because the

weather in Yorkshire is rarely warm enough to live, eat or study outside for

any considerable length of time.

We got our water from public wells that were a couple of miles away and we also had to carry water for the animals which we would pour into purposebuilt ponds for the use of cattle, sheep and goats when we got back to the village. When some people were desperate for water they would be forced to drink from these animal ponds but our family was able to avoid this unsatisfactory practice and through good organisation always had sufficient water. There was no artificial light, not even candles, and we had to make do with moonlight, although sometimes we would light a rag soaked in a bowl of kerosene and that would provide a little light. During the day, if we lived out in the compound, the few trees there would give us protection against the sun. We were not the poorest family in the village, but we had only rudimentary possessions and life had no luxuries. Later, when living at my grandmother’s I was aware that she often went without food to make sure the children, myself in particular, actually got something to eat. We lived in rural poverty in a way that peasants may have lived in medieval Europe and we knew no different because everyone we knew was in the same position.

Like most young children I was unaware of the outside world. The fact that when I was four the Second World War broke out in Europe, and Indian regiments were involved in fighting in the North African desert, totally passed us by. However, by 1944, when the war against Japan came to the eastern gates of India, culminating in the great sieges of Imphal and Kohima, I was more aware of what was happening, especially as some of our family members and neighbours had volunteered to fight, and were involved in that desperate defence of our country and the later campaign in Burma.

When my mother died it was imperative that the family found some suitable female relative to look after me straightaway. My father was not capable of looking after me as he had a full time job. Moreover, it was not expected that men would bring up children by themselves in my country, so he had to make some arrangements for me immediately. His sister, my aunt Said Bibi, had just given birth to a daughter two days earlier, so she volunteered to take me and bring me up with her own family and I could share her own milk with her daughter, and use goat’s milk as a supplement to feed me. So that night I was taken to her village thirty miles away called Barbon, and for the next two years, although I cannot, of course, remember anything of those times, she brought me up with her own family.

This was the way families supported each other, as they did in many other countries that did not have a welfare state. It was understood that it was the family’s responsibility to take care of the less fortunate. Although I was not technically an orphan, but with my mother dead and my father unable to care for me, I was in a very perilous position that could have resulted in a desperate life as a child or even an early death through neglect. So I am grateful to my aunt for taking on the responsibility and I can sympathise with my father, who was only just twenty years old himself, and who within a year had married again, even though he had retained a great love for my mother. He needed to find a wife and begin a new family if he was to play his full part in village society. He later went on to be a clerk to a firm of solicitors and was a man respected in his community to whom people came for advice and support when they had problems with court cases.

Until I was an adult I saw very little of my father, and it was only later that I got to know him better. He now had another family and in the fullness of time he had five children by his new wife. So I have four step sisters and one step brother, whom I got to know when I was older but with whom I had little or no contact when I was growing up. Meanwhile, my maternal grandmother had visited me in Barbon and was very unimpressed with the conditions in which I was living. She persuaded my father to let her take me back to her village and bring me up with her three daughters – my own mother’s younger sisters – who at this time were still only in their teens.

This was one of the most important decisions of my life, yet one I had very little to do with, because I was still not quite two years old. My grandmother treated me as the son she no longer had, and, in return, I always thought of her as my mother, while her daughters seemed like elder sisters rather than aunts. In fact I called her mother until she was quite old and then I reverted to addressing her as grandmother, but she took marvellous care of me and brought me up as one of her own and I lived more completely within the orbit of my own mother’s family.

|

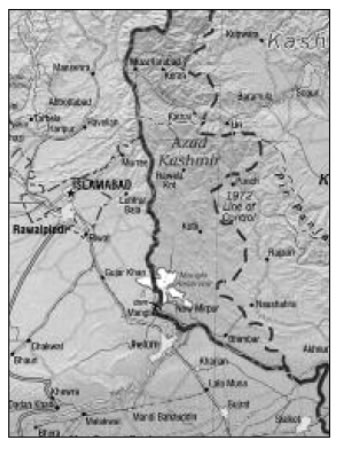

| Map of Azad Kashmir, showing New Mirpur, Jhelumand the Mangla Dam in the lower centre of themap. |

So by the time I begin to have clear memories of my life, I was growing up in a one room house in Gura Domal, a village only six miles from where I was born. It was a village that was similar in size and appearance to Dhangry Bahdur and the people there were subsistence farmers who eked out a living tending their crops in the adjacent fields. By the time I was four and playing with the local village kids, most of whom were related to one another in this small hamlet of about fifteen houses, I started to get bullied a lot by the other children. They would taunt me, calling out that I had no mother, and I became rather depressed about the situation. My grandmother came to my defence, fiercely ticking off the boys involved, then visiting and admonishing their parents if they had been bullying me that day. Ironically, some of these boys ended up in Sheffield and I see them from time to time in the streets around Firth Park, when I am going about my business today.

Challenging the parents of the bullies did not always meet with success; and the bullying continued to be a serious problem for both me and my family. My grandmother hit upon a novel way to resolve the issue. Although she had no interest in education as such, probably believing that a formal school education was not for the likes of villagers in small rural enclaves, she decided that I should go to school—aged four and half years old. The school was six or seven miles away and I had to do that round walk barefoot every school-day, because I had never owned a pair of shoes and the sandy path could be scalding hot from the heat of the unrelenting sun.

“Better if out of sight and then I can have peace of mind!” my grandmother explained as she packed me off to the pre-primary school that operated along the lines of a kindergarten school. It would, however, turn out to be a momentous decision that would change my life forever, and start me on a journey that would lead through schools and colleges to a reasonably well paid position, and eventually to Britain and Sheffield.

By Dr. Choudry M. Walayat MBE

Copyright 2009 - Dr. Choudry M. Walayat MBE

You May contact Choudry Walayat on his Mobile - 07941016417 (UK)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

All rights reserved. No part of this online book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanised, by photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written consent.

Online Copy Published by Nadeem Walayat - Contact admin@REMOVEwalayatfamily.com

Hard Copy Published by Kashaf Walayat - ISBN Number 978-0-9560445-0-1 - Contact on Mob. No. 0044 7766 22 1006

All facts and opinions in this book are the sole responsibility of Dr. Choudry M. Walayat. The book has been written in co-operation with John Cornwell, who produced the final texts of the chapters of the book.