News

Made in England: England Their England - Chapter 4 - Made in England - The Memoirs of Dr Choudry Mohammed Walayat MBE

I had long been intrigued by the British, even though I had never met one of them. How was it that people from such a small country, stuck on the edge of Europe, could have wielded so much power and influence in the world during the previous two hundred years? As an enthusiast for studying history I knew something of the British Empire and especially of their Indian Raj, which they themselves considered the Jewel in the Crown of all their overseas dominions. There was one other rather unusual connection between Britain and myself and that was the name given to me at birth. My mother was called Walayat Begum, and in her memory my grandmother suggested that I should be called Walayat. They probably were also aware that Walayat means England in Urdu, so I was Mohammed “England” and maybe therefore predestined to live most of my life in England.

In 1961 there still had not been large scale emigration to the United Kingdom from Pakistan, but we all knew people who had gone there. When they returned on a visit they adopted the rather superior air of people who had been living in a much more advanced society, or so it seemed to us. I regard the first generation of emigrants as the generation before mine. Men who had been Lascar sailors who had jumped ship and stayed in the UK, or intellectuals and professional people who could afford to get an education at English schools, universities and teaching hospitals and then perhaps stay on in London or other cities, after their education.

British people were on the move as well at that time, with a million opting to go to Australia and professional people looking to further their careers in New York or California. If you were a Commonwealth citizen you could just move to England and live there. In 1961 there was no Immigration Act, and as a added bonus you could vote in British elections, which an American or Frenchman could not do.

All you needed was a passport and some money to cover fares, a bank draft for 2500 rupees (about £280 then) and something to live on when you first got to Britain. This was not as easy as it sounds. Getting a passport in Pakistan for most people was a bit of a racket. People employed agents who, for a sizeable cut, would help people with little education to deal with the Passport Office in Karachi. As an experienced clerk I knew I could handle the application myself, and did so. I found the money for the bank draft, which the Pakistan Government insisted on you having as a form of security. So, if you failed to find a job in the U.K., the money held by the State Bank of Pakistan on behalf of our Government would pay your return flight home.

When the envelope arrived I found a covering letter but no passport, and immediately thought that the agents had had the last laugh and stolen it in transit. In panic, I imagined some fellow sitting smugly on a plane to Heathrow travelling on my passport. However, it turned out to be a genuine error and my passport arrived a few days later, after we had complained. As for the money for the air-fares and travel expenses, this was provided by some very good friends already in England. Abdul Gafoor, who had been a close friend at college, was now living in Birmingham and he kindly paid the money directly to the airline and one day I was delighted to get an envelope containing the ticket. Meanwhile Mohammed Rafique, who had been at Lidder School with me and is still a close friend to this day, sent money to his father for me to collect in Pakistan. Mohammed Rafique was living in Darnall at the time, and my friendship with him is the reason I ended up in Sheffield, where he still leads an active life in Nether Edge. This was the way friends and family helped each other in those days. With this selfless help, poor people managed to overcome the massive obstacles that faced them as they crossed the world to make a new start to their lives. All Abdul Gafoor asked me to bring him was a book on how to cook our native dishes, so he could properly feed himself.

Arrival at London

Arrival at London

Middle East Airlines flew me from Karachi to Heathrow. Like most people at the time I had never flown, nor had I ever been in Karachi let alone London. It was all a great adventure for a man who was only twenty-five years old, with only hopes, but no certainties, of what would happen on arrival. Landing at Heathrow, already the world’s largest airport, was a revelation to me. Everything was on a colossal organised scale and I was enraptured by what I saw. People in the airport smiled and were helpful and though it was crowded, people were self-disciplined and automatically formed queues to get their luggage, to get on the buses or to get something to eat. I arrived with only £2.10 shillings (£2.50) in my pocket, so, to all intents and purposes, I was broke when I got to my new country.

My plan was to go to Victoria Coach Station, then get the first bus to Birmingham, where Abdul Gafoor said he could put me up and where I hoped to find work. The English people at the airport and on the bus seemed like they came from another planet. They looked like supermen, seemed polite and well mannered, kind and helpful. When I asked for information they gave it to me and when I got to London I even asked for directions from a policeman who was extremely helpful. I chuckled to think how I would never have dared ask a policeman in Pakistan for directions while he would have been equally amazed to be asked; he might even have clouted me one for my cheek.

Travelling in from Heathrow was another revelation. Driving along the Great West Road into the centre of London, everyone had their own seat with no one standing and they were plush, padded seats as well. A young woman was reading the Daily Mirror and it was her own individual copy; it was clear it was not going to be passed round and grabbed by everyone else who wanted to read it. The road was a dual carriageway raised on stilts and we approached the centre, via the Hammersmith Flyover, and then drove in heavy, but orderly, traffic past the great museums in South Kensington, each one looking fit to be a palace for a prince. Further on we progressed through the opulent shopping district along Knightsbridge, passing Harrods and on to Hyde Park Corner. This was not Mirpur, nor was it Karachi, this looked a very luxurious country and the women all looked so beautiful and well dressed that I thought they were “fairies from Paradise”. I was soon to learn that not all of Britain was like this and that some people could be less welcoming to newcomers from Pakistan.

Twenty-Four Hours in Brum

On arriving at Victoria Coach Station I straightaway took the bus to Birmingham. I could not afford to buy anything in London let alone stay overnight and my coach fare from Victoria to Birmingham cost an expensive ten shillings (50p), further depleting my small amount of money. On arrival I took a trolley bus to Nechells on the north side of the city centre, to meet my friend Abdul Gafoor at the house where he was staying in Chataway Street. Although he had a college education back home and would have gone on to have a position as a clerk or a teacher, here he was working on the buses, as many Pakistani immigrants did at that time. He was very welcoming, but unfortunately for me the fifteen Pakistanis sharing the three rooms in the house were not. They did not feel they could fit another person in and I was made to feel very unwelcome. It is ironic that these people gave me my first hostile reception since I had arrived in England.

I resolved the issue, because I did not want to embarrass my friend who

had very generously contributed to my fare to the U.K., by ringing Mohammed

Rafique in Sheffield. I did not know how far away Sheffield was or even in

which direction it lay, but he immediately invited me to drop everything in

Birmingham and get a train to Sheffield.

I resolved the issue, because I did not want to embarrass my friend who

had very generously contributed to my fare to the U.K., by ringing Mohammed

Rafique in Sheffield. I did not know how far away Sheffield was or even in

which direction it lay, but he immediately invited me to drop everything in

Birmingham and get a train to Sheffield.

Short sojourn in Sheffield

Rafique’s brother picked me up in his car at the Midland Station and drove me over to Barnardiston Road in Darnall where Rafique lived. I did not realise it at the time, because I had arrived as a bit of a “refugee” desperate for a friendly face and a place to stay temporarily, but I was now in the city where, subsequently, I have spent the majority of my life. Not that the east end of Sheffield was very glamorous in the early Sixties. Rows of depressing brick terrace houses standing cheek by jowl with Victorian steel works and engineering factories, that seemed to have the grime of a century all over them. In my memory it always seemed to be drizzling and smoke and muck hung about in the air, all a far cry from rural Azad Kasmir where I had come from.

Rafique made me most welcome and although they only had three rooms

in the house they packed in ten people, including the English wife of one of

the Pakistani men. In the days and weeks to come I tried to get a job, usually

at the nearby steel works. There were plenty of factories in the Don Valley, for

the steel industry stretched all the way from Rotherham to the city centre,

four miles of factories and a mile deep across the valley. However, there did not

seem to be any jobs for me and often when I got to the enquiry desk in the

office, the staff just waved their hands as if to say “No work here mate!” It may

have been that they thought I could not speak English, or, maybe, it was just

crude prejudice, but Sheffield was becoming a rather inhospitable place for

me.

Rafique made me most welcome and although they only had three rooms

in the house they packed in ten people, including the English wife of one of

the Pakistani men. In the days and weeks to come I tried to get a job, usually

at the nearby steel works. There were plenty of factories in the Don Valley, for

the steel industry stretched all the way from Rotherham to the city centre,

four miles of factories and a mile deep across the valley. However, there did not

seem to be any jobs for me and often when I got to the enquiry desk in the

office, the staff just waved their hands as if to say “No work here mate!” It may

have been that they thought I could not speak English, or, maybe, it was just

crude prejudice, but Sheffield was becoming a rather inhospitable place for

me.

I had to find work, not so much because I needed to send money back home to my family – like so many other Pakistani immigrants who had mothers and younger siblings back home – but because I was living off the generosity of Rafique. He not only shared his small room with me, but bought all my food and whatever necessities I required. I will always be indebted to him for his big-hearted, unselfish help he gave me in those difficult times.

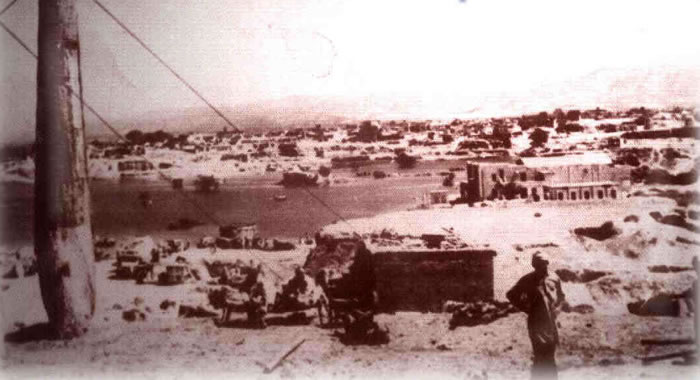

Old Mirpur, which was levelled and is now under the waters of the Mangla Dam. My grandfather was buried by theWestern Gate of the old town.

By Dr. Choudry M. Walayat MBE

Copyright 2009 - Dr. Choudry M. Walayat MBE

You May contact Choudry Walayat on his Mobile - 07941016417 (UK)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

All rights reserved. No part of this online book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanised, by photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written consent.

Online Copy Published by Nadeem Walayat - Contact admin@REMOVEwalayatfamily.com

Hard Copy Published by Kashaf Walayat - ISBN Number 978-0-9560445-0-1 - Contact on Mob. No. 0044 7766 22 1006

All facts and opinions in this book are the sole responsibility of Dr. Choudry M. Walayat. The book has been written in co-operation with John Cornwell, who produced the final texts of the chapters of the book.